Early Years: The Whaling Era at Killisnoo

Baleen whale hauled out at the nearby Murder Cove plant on Admiralty Island

(Case and Draper Collection ASL-P39-0505, Alaska State Library--click to enlarge from source)

----Draft Status: "Gamma"; nearing final completion---

Initial European settlement at Killisnoo appears to have been the establishment of a Hudson Bay Company station (Moser 1899).

The Killisnoo plant was established by the Northwest Trading Company, an ambitious firm from Portland Oregon which sought to establish a foothold in the newly purchased (1867) and rapidly developing Alaska Territory. The NWT began operations at Killisnoo as a trading post in 1878 (U.S. Dept. of Interior 1893). The operation was clearly well financed, constructing shore plants, purchasing vessels and barges, and moving men and equipment around Southeast Alaska with ease, very quickly after the start of its operations. The steamer Favorite was purchased and in 1880 set out for Southeast Alaska under the command of J.W. Keene to support operations there. By the spring of 1881, the new company had established trading posts at Howkan, Killisnoo, Sitka, and Juneau.

With aggressive and opportunistic minds like Captain J.M. Vanderbilt guiding the operations, the sight of whales preying on herring nearby could quickly lead to the development of a shore-based whaling station at Killisnoo, as the U.S. Census Report for 1890 (U.S. Dept. of Interior 1893) records the establishment of the Killisnoo plant:

The enterprise was begun in an experimental way in 1879 by the Northwest Trading Company. The company had established a trading station at Killisnoo in 1878. It was observed that a large number of finback whales frequented the waters of that vicinity to feed on the herring and in 1880 whaling was attempted but was discontinued the same year. The oil and fertilizer business having been found a profitable one it was gradually increased until in 1887 the maximum production of 380,000 gallons of oil was reached.

Although this report provides insight into the reason for establishing the whaling operation, other records document whaling continuing through at least 1882. In fact the bombardment of Angoon in October 1882, involved a harpoon exploding while engaged whaling. (note: Petroff [1884] makes no mention of Killisnoo operations in the "Fisheries" section of the 1880 census.)

The NWT made an enormous investment in the whale reduction plant, perhaps somewhat foolishly, as Scidmore (1883) observes that all of the lumber for the plant was imported into this timber-rich region:

This station represents an investment of over $100,000; the oil works alone having cost $70,000, and extravagant management having doubled all the necessary expenses of the first plant. As there was no water supply on the solid rock of Kenasnow, a reservoir with a storage capacity of 90,000 gallons of water was constructed; and with cedar forests on every side every bit of lumber used was brought by freight from below.

While the main focus of the operation is reduction for oil products, some cod were also salted or dried, and some herring may have been salted. At some point around 1882, a decision is made to switch the reduction operation from whaling to herring, though there are varying accounts as to the reasons for the switch. Eliza Ruhamah Scidmore provides one of the few observations of the switch from whaling to processing herring, as well as of the above initial investments in the plant. Scidmore was a pioneering travel writer (and later a National Geographic board member) travelling through Southeast Alaska in 1883 (on the propeller steamer Idaho) and again in 1884 (on the sidewheeler Ancon). Scidmore (1885) had made note of the abundant herring in Chatham Strait, and paints a descriptive snapshot view of Killisnoo at the moment of her visit(s):

On this little island of Kenasnow, the Northwest Trading Company has its largest station, Killisnoo, where codfish are dried, herring and dogfish converted into oil, and the air weighted with the most horrible smells from the fish guano manufactured there. The company has extensive warehouses, works, and shops on Kenasnow, and around the buildings there are gathered quite a village of Kootznahoo Indians who are employed at the fishery.

Killisnoo was first established as a whaling station but many causes decided the company to abandon that branch of fishery. There is a tradition that the Indians once regarded their great totemic beast, the whale, with such veneration that they would never kill it, nor eat of its flesh and blubber. The Kootznahoos have grown skeptical in many ways, and they made no objections to harpooning the whale, until the bomb exploded in 1882; and after the troubles following upon that impious adventure, the company decided that whaling was not a profitable business, and began to fish for cod and smaller fry.

Scidmore 1885 implies here that the harpoon explosion, and the subsequent melee of the bombardment, had much to do with the switch from whales to herring. She would have heard this tale either 9 months or 21 months after the incident, which must have still been fresh on the minds of those she apparently spoke to. Whales appear to have remained abundant in the Chatham Strait area, because they attracted additional shore-based whaling effort two decades later at Murder Cove, and at Port Armstrong, both of which would subsequently be associated with herring reduction plants.

Webb (1988), in his treatise on commercial whaling in the north Pacific writes:

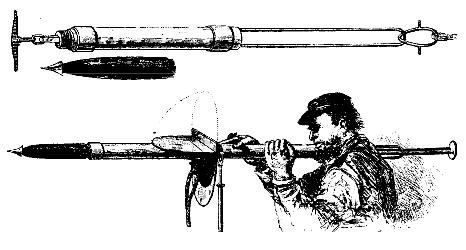

...the Northwest Trading Company of Portland Oregon appears to have engaged in shore whaling from its post on Killisnoo Island in Chatham Strait about 1880. The operation enjoyed very little success; a bomb gun explosion -- perhaps it was a California Whaling Rocket --(cached) -- killed two (sic) men, and after a few years the company abandoned whaling in favor of the herring fishery.

The California Whaling Rocket Harpoon, invented about 1827, protected the face of the whaler when he fired his weapon. (after Roemer 1996; originally from the California Historical Society, San Francisco, California)

Regarding the plant switching from whales to herring, the 1890 Census Report (U.S. Dept. of Interior 1893) observes:

Killisnoo was first established as a whaling station, but after difficulties with the natives the catch was changed to herrings, which are much more easily secured and managed.

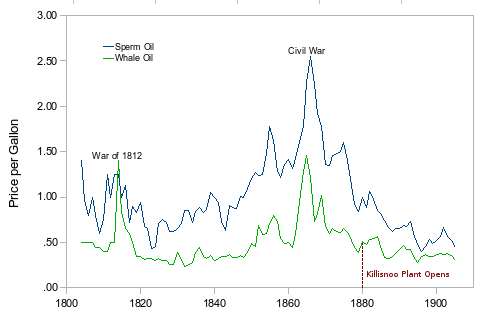

Figure __. Price of sperm and (other) whale oil, 1804-1905. Data extracted from Starbuck (1878) for 1804-1843 (p. 660), and from 1843-1905 from the "Whaleman's Shipping List", as cited in Tower (1907). For an inflation-corrected interpretation of the 1804-1878 portion of these data and a Huppert Cycle analysis, see Bardi (2004).

It was likely that declining whale oil prices contributed to the decision to switch from processing whale oil to herring oil. Whale oil prices had spiked during the civil war but were falling rapidly (Figure ___) as the Killisnoo plant began operation. The price of whale oil continued to fall as oil consumers switched to less expensive petroleum-based products. The last application for whale oil in the U.S. was for high-quality, non-congealing lubricant, with distribution finally ending in 1978 when sources were no longer available. Entering the whaling industry was a risky proposition well before 1880 -- the U.S. whaling fleet had already declined from 735 vessels in 1846 to only 39 vessels by 1876.

On the east coast of the U.S. in the 1870s there was continued interest in producing oils, even though the prices were declining; menhaden oil (produced in a reduction process similar to that for herring) was "interchangeable" with whale oil (Webb 2001, Reeves et al. 2002). When menhaden abundance declined sharply in the Gulf of Maine in the late 1870s, some fishermen, and their steamers, converted to whaling; when menhaden reappeared in the Gulf of Maine in 1886 "steamer whaling lost its appeal and most of the steamers returned to fulltime (menhaden) fishing" (Reeves et al. 2002). Scidmore (1885) notes that the Killisnoo plant managers (likely Vanderbilt and DeGroff, who were both born on Staten Island) were experienced in reduction processing of menhaden. Here we have a close correlation between east and west coasts in the pattern of activity during the initial years of the Killisnoo plant. The fact that in 1880 many of the New England menhaden plants had closed because of low menhaden abundance (Johnson et al. 1915) could well have prompted the Northwest Trading Company to investigate replacement oils, both whale and then herring.

Southeast Whaling Photo Gallery...

Back to: History of Southeast Alaska Herring Fisheries

Link to: References

Caution: These pages contain preliminary research results, and are presented here only to further collaborative research and analysis. The information presented has not been fully analyzed or verified for correctness. Please consult the original literature citations for authentic interpretations or contact the author regarding applications of any analysis presented on these pages.

For more information, contact Fritz Funk:

fritz funk.io

| Last modified: Apr 12, 2008 at 21:14:42

funk.io

| Last modified: Apr 12, 2008 at 21:14:42